As disco dominated the popular music scene in the USA and the Swedish pop group ABBA won the Eurovision Song Contest in Brighton, UK, with “Waterloo” (1974), over one hundred thousand guest workers in over three hundred locations in Germany went on a “wild” strikes in the early 70s. “Wild” not in the sense of “crazy”, but “illegal”. The once submissive Turks, Greeks, Italians and others, who had gratefully accepted any kind of menial labour, grew rebellious. Suddenly they became the Frankenstein Monsters of the economic miracle, unabashedly demanding equal pay for equal work under humane conditions - with women at the forefront, by the way.

“Are the guest workers taking over?”

Bild Newspaper, 29th August 1973

The strike at the Ford factory in Cologne was the largest ever to have taken place in Germany. Twelve thousand mostly Turkish-born workers, occupied the plant for five days and nights. They ignored multilingual announcements in the Cologne trams, Chancellor Willy Brandt’s appeal to common sense and Turkish diplomats outside the factory gates who called on the workforce to cancel the strike. Worst of all was the smear campaign in the media. According to the Allensbach Institute in October 1973 only eight per cent of the population did not know the name of the Ford strike spokesman, Baha Targün.

“Baha’s rhetorical brilliance and his youthful charisma, reminiscent of Che Guevara, or the other revolutionaries of 1968, of Jesus even, are inextricably linked to the fascination of the Ford strike.”

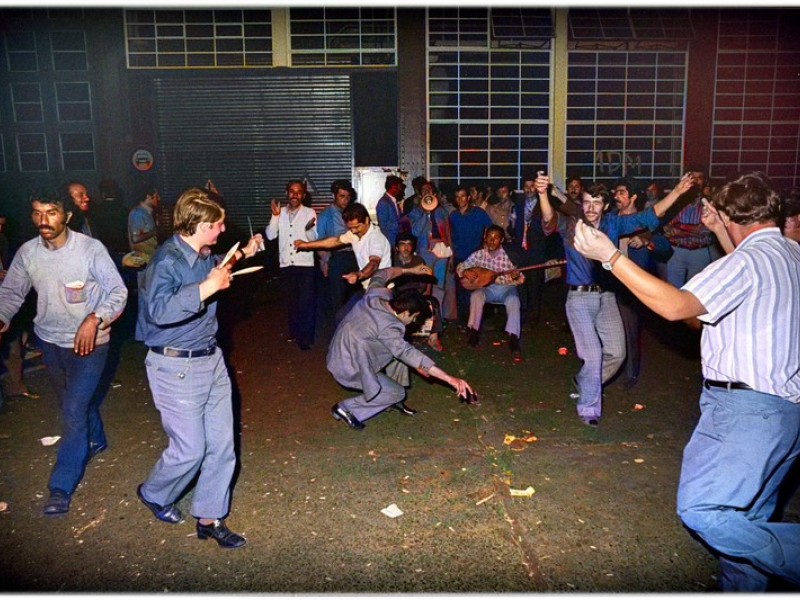

Baha spoke German, had charisma and was able to present himself in a convincing manner. He held talks with the works council, which, incidentally, was clearly opposed to the “wildcat” strike. He issued press releases, convinced the workforce day after day of the necessity of the struggle and joined in with their communal singing. The fact that the strike was brutally crushed on the fifth day, along with the help of strikebreakers armed with truncheons hired from Belgium and members of the plant security force, plant managers and the police, is attributed by some strikers to the fact that Baha Targün’s legendary megaphone was conveniently destroyed and his hoarse voice could no longer be heard.

Two years after the Ford strike, Baha Targün was charged with alleged “predatory extortion” and “dangerous bodily harm” of a Turkish businessman and sentenced to six years in prison by judge Victor Henry de Somoskeoy. Local lawyers and journalists from the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger newspaper expressed considerable doubts about the charges and the judgement. Was this political revenge? A year earlier the same judge had sentenced Beate Klarsfeld, who hunted down high-ranking Nazi functionaries and uncovered Kiesinger’s Nazi past, to two months in prison.

The five years that Baha spent in the prisons of Cologne-Ossendorf and Remscheid are also part of the story of “Baha and the Wild Seventies”.

Baha Targün was once comparable with the revolutionary Cohn-Bendit for the people of Turkish origin. But he and many other protagonists of the 1973 strike wave have been forgotten. This is because the official history ends with the suppression of the strike.

According to this shortly afterwards the recruitment ban was introduced. But one could also have added, this is how the guest workers fought for their dignity. Max Frisch once said: “Workers were summoned, people came. Now is the time to recognise that these people not only contributed to Germany‘s Economic Miracle, but are they also part of the history of German democracy.

“Baha and the Wild Seventies” is based on oral and written memories. As part of the research, we interviewed Baha’s family and his friends, including many German nationals. Two pensioners who were on strike at Ford at the time are actually part of the production. One could describe the musical as a form of documentary theatre however it was always conceived in the form of rock opera similar to Ken Russell’s music film Tommy, based on the concept album written and performed by The Who. In any case, the legendary nights in Ford’s upholstery warehouse were pure rock’n’roll.

“They discussed, voted, sang, played music, prayed, danced, ate together, organised and listened to Turkish fairy tales.”

The musical framework for the show are original songs especially composed for it. Main composer Nedim Hazar, singer and song writer of the German-Turkish cult band Yarinistan from the 80s, revives the unmistakable sound of his former band here. There is also room for Turkish evergreens such as “Aldırma Gönül”, an empowerment song for prisoners by Turkish writer Sabahattin Ali. Incidentally, Ali was dramaturge for the famous theatre director Carl Ebert, who fled Nazi Germany and founded the state theatre of Ankara.

The music, containing modern rap interludes influenced by singers such as Janis Joplin, the group Ton Steine Scherben and Barış Manço, is played live by a rock band, but with two cellos in the foreground. Both Anatolian dances and “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose” sound different here. According to the Cologne journalist Felix Kopotek, Janis Joplin’s songs could well have been part of the Ford strike repertoire. “Tanz auf dem Rücken des Tigers” is the title of his article in the Kölner Stadt Revue, which fittingly describes the feelings of the strikers: “This explosion of liberation, this sigh of relief - if that would set a precedent, if the spark would ignite! Unimaginable.”