In 1969, shortly after I was born, my father came to Cologne as a so-called “guest worker” and immediately found a job at the Ford plant.

Prof. Dr. Kemal Bozay

What do the 1970s stand for?

What do the 1970s stand for? Many people think of it as a “wild” time - and not without reason. It was an period full of exciting and turbulent events such as the oil crisis and the Watergate Scandal, but the decade was also characterised by exuberant moments such as disco fever and the flower power movement. However there was something else, something wild, that had a lasting effect on the migrant strike culture and their struggles for recognition, especially in Germany with the “wildcat strike” at Ford in Cologne and the Pierburg strike in Neuss in 1973. These strikes were not only short and violent, but also continue to characterise the migrant culture of remembrance in Germany to this day.

These events also have a personal significance for me. In 1969, shortly after I was born, my father came to Cologne as a so-called “guest worker” and immediately found a job at the Ford plant. He worked there until 1973 before moving to a job in the chemical industry at Bayer Leverkusen shortly before the “wildcat strike”. Even as a child, we often talked about the strike at home, so it had a lasting effect on me from a young age. My father repeatedly told me how “Fordism” embodied a very special form of hard capitalism: “It was pure capitalism!”. These stories left their mark on me and later inspired me to look more closely at the subject in my academic career.

In my studies on “Political Education in the Migration Society” at the University of Cologne, I have also tried to offer students insights into the culture of rememberance in the migrant society. There is no doubt that the Ford strike in 1973 is an important milestone in the history of memory, not only of migration, but of society as a whole. Through research, films, text analyses and eyewitness accounts, I also confronted students with the “wildcat strike” at Ford in Cologne. This often led to an aha effect, as this strike represented a different form of strike and dispute culture that still resonates in the local culture of remembrance.

“Wildcat strike”?

A “wildcat strike” is an act of courageous industrial action in which workers independently lay down their tools, without the official support or approval of their trade unions. In August 1973 at the Ford Works in Cologne, in a moment of intense determination and solidarity, workers mainly of Turkish origin spontaneously decided to walk off the job and demonstrate their power to fight for their rights. It is therefore considered the largest labour dispute in German history to be led by migrant workers and was accompanied by an occupation of the Ford plant. It was an expression of deeply felt injustice and a powerful signal that they could no longer be ignored. This is why this form of resistance is often referred to as a “spontaneous strike”.

The moments of resistance

It was a hot summer when the shop floors of the Ford plant in Cologne, starting with the Y shop floor, were transformed into a battlefield for justice and recognition. The machines that normally dominated the production lines, fell silent. Instead, the shouts of thousands of workers echoed through the halls, determined to express their outrage and protest against injustice.

Turkish workers had been working hard at the Ford plant in Cologne since 1961. They were part of the labour recruitment agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and Turkey and made up about a third of the entire workforce there by 1973. But their work in the factory was defined by oppression, discrimination and heteronomy. They were among the unskilled labourers in the final assembly line, and were placed in the lowest wage groups and were poorly represented in the works council. It was a form of isolation whereby the Turkish workers were marginalised, defined by daily hardship and the invisible stigma of the “guest worker”.

In August 1973, the tension reached its peak. 300 Turkish workers who had returned late from their holidays, were dismissed without notice. Travelling to Turkey at that time was a strenuous affair, often involving a long journey by car, and it was difficult to exactly plan the return date. In previous years, workers had always been allowed to compensate for their absence by working extra shifts. But that year, the management decided otherwise. News of the redundancies spread like wildfire and triggered a huge wave of outrage.

“We’re downing tools!”

On Friday, 24 August 1973, 400 workers of Turkish origin on the late shift spontaneously demonstrated on the factory premises, demanding the reinstatement of their dismissed colleagues and they were met with a wave of solidarity. Shortly afterwards, the entire late shift - 8,000 workers, mainly people of Turkish origin as well as German colleagues - walked off the job. This spark of protest ignited a fire and a cascade of demands followed. One DM more per hour, a reduction of the assembly line speed , an increase of annual leave to six weeks and the end of the special lowest wage groups. A broad front of resistance formed, but it was ultimately the workers of Turkish origin who formed the core protest.

When the early shift of 12,000 workers also supported the strike on the following Monday 27 August, the management was confronted with an unprecedented uprising. The strikers, who increasingly distrusted the works council and the shop stewards, elected their own strike committee, led by a colourful personality whose name would go down in history. Baha Targün. He was also the one who declared the strike with the following words: “We are laying down our tools - there is a strike here!”. While the works council did not support the wildcat strike and called for work to resume, the strike committee resolutely stuck to its demands. It was a fight for dignity, recognition and justice that questioned the power relations on the shop floors of the Ford plants and also challenged the concept of Fordism.

This was unique in German strike history at this time. The resistance at Ford was unprecedented territory for many of those concerned. This was due to the fact that negotiations did not take place at tables, but instead on the “roofs of the Ford plants”. The workers of Turkish origin celebrated their strike with an oriental halay dance. Even the well-known Cologne musician “Klaus, the Violinist” showed his solidarity with the strikers in front of the main gate entrance and accompanied them with a song he had composed himself. For the Ford bosses, images emerged of Anatolian vivacity. They were not used to something like this. The self-confidence of the Turkish „guest workers“ was also confusing for them. There was hardly any sign of the idyllic atmosphere that had previously prevailed at Ford. Another sight not to be forgotten was the employer’s negotiations on 29 August, when they climbed onto the roof to negotiate with the strike leader Targün, who, equipped with a megaphone, was crouching on a pole 10 metres away. Thousands of strikers gathered below him and listened to his words. When he conveyed the employers’ “no” to their demands, that their colleagues should not be dismissed and their hourly rate of pay be increased by 1 DM more, Targün then shouted to them “The strike continues!“ The strikers responded with resounding jeers and whistles. Bitter angry looks flew towards the very roof of the Ford factory, where the bosses, these gentlemen, looked down into the crowd, perplexed.

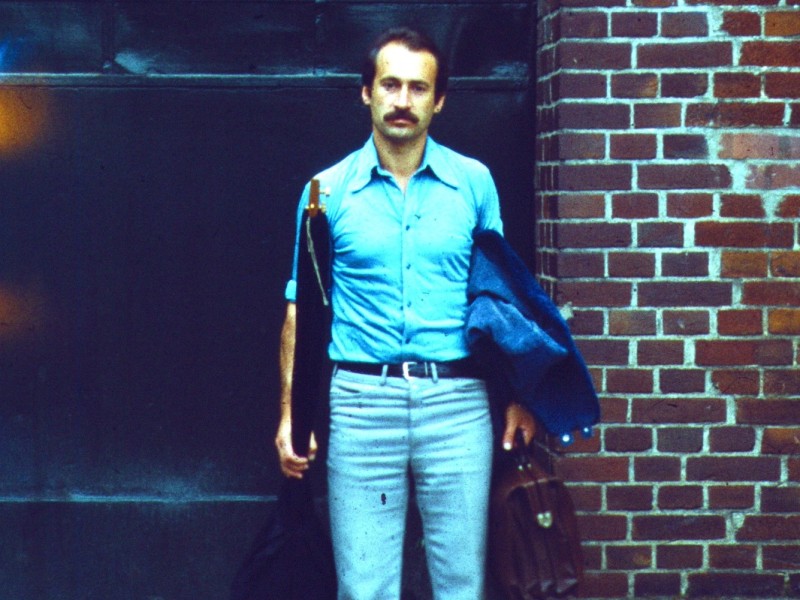

The face of the strike: Baha Targün

The important figurehead of this strike was undoubtedly Baha Targün. Although he had only been employed at Ford for a few months, he was recognised by the Turkish workers as a natural leader and was spontaneously elected strike spokesman. Targün, a man of quiet but forceful words, proved to be exactly the right person to motivate his compatriots and make the management understand the determination of the strikers. He was not an experienced trade unionist nor long-time labour leader, but a politically active person who rose above himself in an extraordinary situation and led this strike through to the end. His name became a symbol of migrant struggles for recognition that reached far beyond the walls of the Ford plant and took a firm place in the history of migrant labour struggles in Germany.

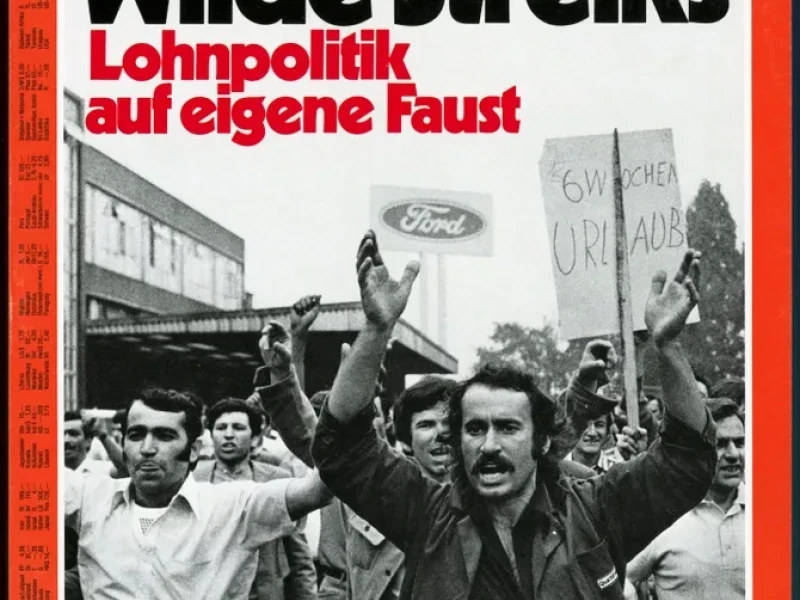

The media established Targün as symbolic of the strike. On 3 September 1973, “Der Spiegel” ran the headline “Wild strikes - wage policy on your own” and published a picture of him marching through the Ford plants at the head of a demonstration. This picture was more than just a snapshot of a strike - it was a symbol of the resistance that brought the 1973 strike wave to the public’s attention. Despite the fact that this wave of strikes ultimately did not end victoriously, Targün played a decisive role in paving the way for the politicisation of so-called migrant workers in the years that followed.

A brutal crackdown

On 29 August, the fifth day of the strike, the management made a compromise offer: a review of the sackings and a cost-of-living allowance of 280 DM for each worker. However the workers rejected the offer by an overwhelming majority. But the determination of the strikers was to be put to a brutal test later that day.

A “counter-demonstration” formed. It consisted of foremen, supervisors, plant security staff, strikebreakers from Belgium and the police. They carried truncheons and brass knuckles and were determined to break the strikers’ resistance. The strike was put down by force, the strike leaders were hunted down and finally handed over to the police. Baha Targün, who had acted as a symbolic figure in the strike, was years later deported to Turkey. He was also seriously injured during the violent counter-demonstration. His actions, his courage and his determination are inextricably linked to the events of that summer.

The German public observed the events with mixed feelings. The Bild newspaper spoke of the “Turkish terror at Ford” and reported that alleged communists had sneaked onto the factory premises. The chairman of the Ford works council at the time, Ernst Lück, accused “radicals from the university” of having fuelled the situation at Ford. For the striking workers however, it was a fight for more than just wages and working conditions - it was a fight for their dignity and their rights in a society that often only perceived them as strangers.

A legacy of resistance

The Ford strike of 1973 did not end in victory. The consequences were extreme. 27 alleged “ringleaders” - including Baha Targün - were arrested and prosecuted, over 100 workers were sacked without notice and a further 600 were forced to resign. But the strike had made a difference. The Turkish workers had shown that they had, power and they fought their way deeper into German society in the years to come. The racist division of the working class could not be overcome, but the strike left a legacy of resistance that still resonates today.

This strike was part of a larger movement that swept through the German labour market in 1973. There was also a major industrial dispute at the Neuss-based automotive supplier Pierburg in the same year. Workers, mainly from Yugoslavia, Spain, Turkey, Greece and Italy, this time with the support of the trade union, demanded the abolition of the low wage group 2 and a pay rise. This strike was also characterised by a heavy hand, but it led to success: low-wage group 2 was abolished and wage increases were introduced.

The Ford strike was therefore more than just a labour dispute. It was an uprising against marginalisation and discrimination, a rebellion against the injustices faced by migrant workers. And although this strike was violently suppressed, it remained a symbol of the unbroken will for change. Baha Targün, the face of this resistance, reminded people that a fight for justice does not always have to be successful to be significant. He fought for many, and his legacy lives on in the memories of all those who refuse to resign themselves to a life on the margins of society.

The fate of Baha Targün

After the strike was over, the life of Baha Targün, who had unselfishly fought for the rights of his colleagues at Ford, did not go well. In a questionable trial before the Cologne Regional Court, presided over by Victor Henry de Somoskeoy, then notorious as a harsh and extreme judge, Targün was found guilty in 1975 of a crime that the press described as unbelievable and he was imprisoned for six years. The arch-conservative Cologne judge Somoskeoy, also known to the public as “Victor Henry against all”, was far from merciful in all his proceedings. For example, he “hunted” the well-known writer Heinrich Böll, who criticised a case brought by his chamber concerning an assault by young communists on an NPD stand in Cologne-Nippes as one-sided. Somoskeoy also condemned Beate Klarsfeld, known as a Nazi hunter. She is said to have attempted to kidnap an SS Obersturmbannführer in Cologne-Holweide. The judge’s list of “victims” is long. The “victim” Targün was finally deported to Turkey in 1979.

Targün only realised from afar that the “Wildcat Strike”, as rigorously as it was crushed, was a vital boost for the trade union movement and workers’ rights in the years to come - along with the success of the women at Pierburg. He became a journalist, author, screenwriter for television and discovered his new passion: climbing. Before retiring in 2008, he worked full-time as a tour guide. Baha Targün died on 17 July 2020 in Zonguldak Hospital following a climbing accident in Kastamonu. His commitment, his will and his pioneering role in the workers’ struggle of the 1970s will remain in our thoughts forever. He has become an essential part of the culture of remembrance.

And in 2025, his story will be central to an original stage musical. Nedim Hazar, founder of the artistic group, Sanat Ensemble, will bring various moments of this contemporary history to the stage via theatre and music under the title “Baha and the Wild Seventies”. This will be an important contribution to the culture of remembrance.